Nonviolence: Tip of the Spear

(This article establishes a moral foundation derived from Einstein’s theory of Special Relativity for the full spectrum of action based on environmental considerations against an oppressive regime. Also published on Medium.)

The supreme art of war is to subdue the enemy without fighting. - Sun Tzu

Nonviolence is a political action theory that advocates for creating political change without the use of physical violence. Nonviolence has been successfully deployed in several movements around the world as part of a portfolio of activism. Proponents of nonviolence frequently emphasize the spiritual benefits of this method. However, nonviolence also holds powerful material benefits as a program of action.

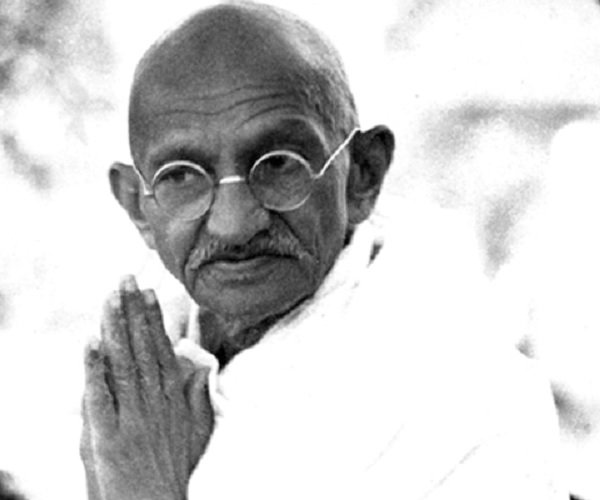

Nonviolent theorists emphasize the point that even in nonviolence there is a type of aggression and force being implemented. Mahatma Gandhi, an Indian activist, is one of the key developers of nonviolent theory:

If by using violence, I force the government to repeal the law, I am employing what may be termed body force. If I do not obey the law and accept the penalty for the breach I use soul force. It involves a sacrifice of self. If this kind of force is used in a cause that is unjust only the person using it suffers. He does not make others suffer for his mistakes.

Gandhi describes how there is still a type of force, however the primary target of this force is inwards as a sacrifice of the self. My definition for violence would be “the reduction of autonomy for external agents”. With this definition, violence is impossible to avoid. Merely by existing, the essential agency of another is altered. We must now be taken into account to their planning. Even if I am not physically stopping an oppressive soldier, I am still forcing them to alter their intended trajectory of expression.

Aggression and assertion of will is inevitable when seeking an accelerated shift of the prevailing order; the nonviolent theorist looks for ways to express this aggression without direct bodily harm. Rev. Martin Luther King, an American minister, describes his view on the importance of nonviolence when seeking a peaceful outcome:

So, if you’re seeking to develop a just society, they say, the important thing is to get there, and the means are really unimportant; any means will do so long as they get you there — they may be violent, they may be untruthful means; they may even be unjust means to a just end. There have been those who have argued this throughout history. But we will never have peace in the world until men everywhere recognize that ends are not cut off from means, because means represent the ideal in the making, and the end in process, and ultimately you can’t reach good ends through evil means, because the means represent the seed and the end represents the tree.

King describes his belief in the importance of including the final desired state within the process itself. However, there are those who believe that there are times when creating peace through nonviolence is impossible.

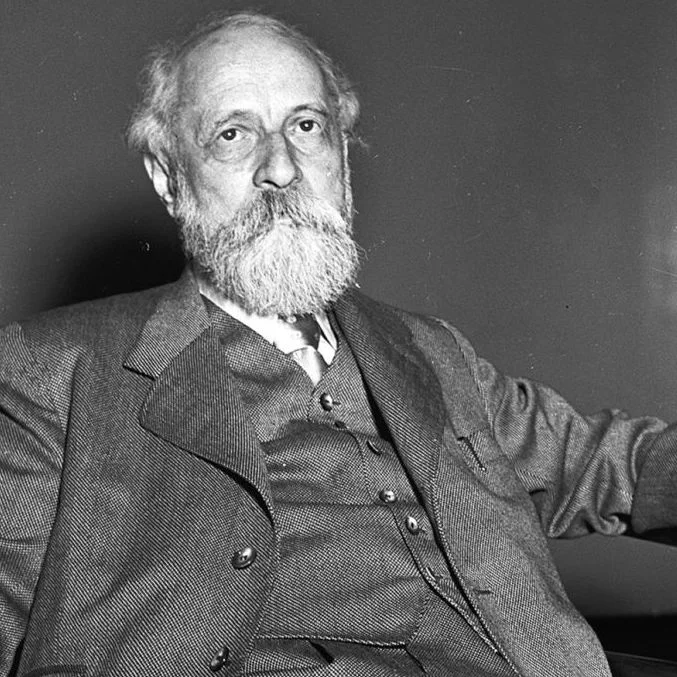

Martin Buber, a Jewish philosopher, disagreed with Gandhi over the viability of nonviolence for the Jews of Nazi Germany:

In the five years I myself spent under the present regime, I observed many instances of genuine satyagraha among the Jews, instances showing a strength of spirit in which there was no question of bartering their rights or of being bowed down, and where neither forces nor cunning was used to escape the consequences of their behavior. Such actions, however, exerted apparently not the slightest influence on their opponents. [….] There is a certain situation in which no “satyagraha” of the power of truth can result from the “satyagraha” of the strength of the spirit. The word satyagraha signifies testimony. Testimony without acknowledgement, ineffective, unobserved martyrdom, a martyrdom cast to the winds — that is the fate of innumerable Jews in Germany.

Buber describes how although he saw many Jews implement the ideals of satyagraha, he was unable to see a meaningful effect to their actions and doubts whether nonviolence could have played any sort of meaningful role against the Third Reich. What can account for this difference in the viability of nonviolence in different campaigns? Why was nonviolence appropriate in colonial India or the segregated United States but not in Nazi Germany? To understand this question, nonviolence as a program of action must be considered for not only its spiritual dimensions, but also its material dimensions.

Two major perspectives on the evolution of history is the Hegelian perspective that consciousness creates institutions, and the Marxist perspective that institutions create consciousness (McDermott). Another way to describe these perspectives is that Hegel privileges energy as the root of matter, while Marx privileges matter as the root of energy. My view is that it is of crucial importance to hold both matter and energy on equal footing rather than prioritizing one over the other. I believe this is the only ethical perspective for an integral worldview given how many different cultures throughout history have upheld one or the other as being primal and I do not believe any human is in the position to definitively articulate an argument for one side over the other. In addition, Einstein’s theory of special relativity, E = mc², reveals an intricate equality between matter and energy that was unknown to either Hegel or Marx.

Nonviolent action can be considered within certain world views as the most beneficial path from a spiritual or energetic perspective with regards to the development of individuals, communities, and ultimately the anima mundi.From this perspective, even if one set of peoples is destroyed from the planet, their legacy lives on and is conserved by the awareness of the world soul. However, this energetic reason is not enough if nonviolence is to be approached from an integral perspective. From the material view, it is important for individual groups and peoples to live on. The survival and success of individual units becomes at least as meaningful, if not more, than the development of some theoretical world soul.

So was nonviolence as a program of political change only successful in places like India and the United States because behind these movements lay the threat of real violence as articulated by their respective militant wings (Subhash Chandra Bose in India and Malcolm X in the United States)? My view is that physical violence was only part of the story when deconstructing why nonviolence worked in some places but not others. The potential for violence — which I describe as “militant potential” — is only one part of the wider ecology within which nonviolence is taking place. Militant potential is the material dimension of the cology, and is tied not merely to the size or potency of a force, but more specifically is connected to the capacity of this force to deal crucial economic blows to the reigning system. The energetic, or spiritual, dimension of the ecology can be described as “moral authority”. Moral authority is the perception of the body politic that one’s struggle is on the right side of history. This appraisal is frequently reflective of the deepest aspirations of the reigning system.

Without a suitable material and energetic context, I believe that nonviolence as a program of political change may be too risky to be the sole category of activity. Given the shifting nature of ecology, nonviolence is best deployed as part of a broader portfolio of activity. In some situations, nonviolence may be completely ineffective. Here is a grid that lays out a model of revolutionary activity based on ecological considerations.

This grid describes how the Jewish condition in Nazi Germany may not have been a suitable candidate for nonviolent action. The Jews had neither meaningful leverage to economically disrupt the Nazi war machine, nor moral authority within a Third Reich which viewed Jewish existence as antithetical to German ascendency.

The Jewish condition stands in contrast to the situation faced by Indians and black Americans. Both of these communities had a fair degree of militant potential as a meaningful capacity to disrupt economic flows. In addition, both Gandhi and King appealed on a moral level to self-concepts baked into the antagonizing power. In Gandhi’s case he used legal concepts and procedures, along with the idea of rights afforded to subjects of the British empire. King appealed to the founding documents of the United States regarding equality.

It is worth noting that just as militant potential can be built over time, nonviolent activism engenders greater moral authority over time as witnesses experience the depth and authenticity of commitment to an ideal. Examples of moral authority growing over time include how civil rights legislation in the United States was fast tracked after the death of four girls at the 16th Street Baptist Church. A modern example would be Malala Yousafzai and the way her work advocating for gender equality gained greater focus and sympathy after she was attacked by the Taliban.

Nonviolence has powerful spiritual benefits. However, to approach nonviolence from an integral perspective, it is important to also take a look at the material benefits of nonviolence as well. When going up against a large, entrenched force, it is very difficult to engage in conflict head on. This has led to the development of irregular military doctrines such as guerilla warfare and nonviolence. Nonviolence is highly cost effective as it requires a relatively small upfront capital expenditure on tools and training as compared to conventional fighting. This means that nonviolent campaigns can be deployed relatively quickly, in multiple geographies, and without the need to engage in risky smuggling or supply chain management. The most aggressive nonviolent actions are often publicized broadly in the light of day. Also, nonviolent soldiers are less likely to be killed in the line of duty, thus minimizing attrition. The overall economy of a nonviolent campaign means that it can be launched with less upfront investment of capital and training, it can be sustained over a longer period of time with minimal casualties, while at the same time cultivating the perception of moral authority. Also, effective nonviolent activism also makes for great content that is willingly picked up by news outlets and distributed to millions of people.

One can only wonder, would the British have left India eventually without the wreckage on their hands at the end of World War II? How important or unimportant is nonviolence? My belief is that nonviolence was an integral part of the overall campaign for political transformation. Nonviolence became even more effective as Indian militant potential increased in the face of a relative decline of British power. When contemplating nonviolence, one must consider both the spiritual and material benefits of not only the action, but also the ecological context. The revolutionary strategist must consider how global, local, and self-initiated events may serve to shift the ecological context, and so necessitate the reprioritization of alternate strategies on the fly. For this reason, nonviolence is best deployed as part of a portfolio of resistance strategies.

Works Cited

Buber, Martin. “Jerusalem, February 24, 1939.” Letter to Martin Buber. 24 Feb. 1939. MS. N.p.

Gandhi, Mohandas, and Louis Fischer. The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas. New York: Random House, 1962. Print.

King, Martin Luther, and James Melvin Washington. A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings of Martin Luther King, Jr. San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1986. Print.

McDermott, Robert. “Nonviolence and Forgiveness.” California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco. 2016. Lecture.